Systems, Signals, and One of One

Over three decades, I’ve learned what it means to build things that outlast their moment.

My work, dimensional reliefs that are code-generated and hand-assembled, is a return to first principles. To understand why I make physical generative work now, you need to know where the obsession with systems and craft began.

Islands and Impossible Machines

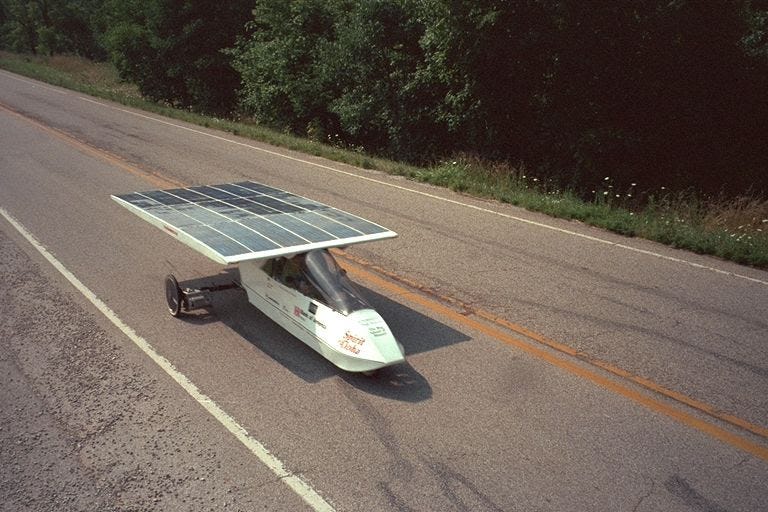

In 1993, I was a senior at Konawaena High School on the Big Island of Hawaii. While most teenagers were figuring out college applications, a small group of us were building a solar car. Not a model, a real vehicle that we would eventually drive across the continental United States powered entirely by sunlight.

The Big Island taught me something about constraints and beauty. Volcanic rock, ocean, elevation gradients that change climate every fifteen miles. You learn to work with what’s there, to design for systems you can’t fully control. The solar car project was the same: we had limited panel efficiency, unpredictable weather, and a route that crossed deserts and mountain passes. Everything had to be calculated, tested, optimized. Form followed physics.

We made it across the country, traveling 3,471 miles in 41 days. But what stayed with me wasn’t the accomplishment, it was the process. The way elegant solutions emerge when you strip away everything unnecessary. The satisfaction of building something tangible that performs exactly as designed.

Console Wars and Digital Craft

By the late 1990s, I’d gotten a degree in Industrial Design and moved into digital spaces. I joined Xbox as Creative Director during the most critical period in gaming history, the console wars between Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft. This was pre-launch through the introduction of Xbox Live, and my focus was the web experiences: how millions of people would first encounter this platform online.

We were building a new category. Gaming had been niche; we were making it central to digital culture. Every design decision mattered. Every pixel on those early Xbox.com pages was a promise about what the platform could be. We were creating language, visual systems, interaction patterns that would define how people thought about connected gaming.

What I learned at Xbox: brand is infrastructure. It’s not aesthetics layered on top, it’s the underlying system that makes everything else possible. The best creative work is indistinguishable from strategy. You’re designing for scale, for engagement, for millions of encounters you’ll never see.

I left after Xbox Live launched. The work was done. Time to build something else.

Civic Infrastructure

In 2010, I co-founded the BIG Idea Lab in Bellingham, Washington. Twelve members of the Bellingham Angel Group capitalized it. The thesis was simple: the Pacific Northwest needed infrastructure for early-stage companies outside of Seattle. We wanted to prove that thoughtful capital and mentorship could work at a smaller scale.

The incubator became a laboratory for early startups. We backed companies working on problems that mattered, many ideated by college students.

Inside that environment I co-founded ActionSprout, which we launched in 2012 and exited in 2018. We built tools that helped 150,000+ nonprofits and political candidates in 72 countries manage Facebook during the platform’s peak influence. Cause marketing, grassroots fundraising, advocacy campaigns. ActionSprout became the infrastructure for how movements organized and advertised on social networks.

What I learned during this era: technology is never neutral. Every platform encodes values. Every tool shapes behavior. When Facebook changed algorithms, thousands of organizations lost their primary communication channel overnight. We’d helped build dependency, and that came with responsibility.

After the 2020 election I stepped back from social platforms entirely. The tools I’d helped pioneer had been weaponized. The infrastructure had outgrown its original purpose. It was time, again, to move on.

Early to Everything That Mattered

Throughout this period, I was exploring parallel tracks. I’d been an angel investor for twenty years, and my pattern has been consistent: early to technologies before they have names, before consensus forms, before the market understands what’s possible.

In the very early days of Bitcoin, I was mining with an ASIC server in my basement. Not because I was chasing returns, I was fascinated by decentralized consensus. The idea that value could be created through cryptographic proof and distributed verification felt like a fundamental reimagining of trust.

When NFTs emerged, I became a bestselling generative artist on the Tezos chain. This was before the 2021 bubble, before mass adoption, when the space was still about artists and collectors genuinely interested in programmable provenance. I was writing code that generated visual outputs, but with a twist, they had blueprints that I turned into physical artifacts that could be permanently displayed in real life.

I watched the NFT market explode, then collapse. I watched AI rapidly move from research labs to consumer applications in months. I’ve seen three complete technology cycles—from emergence to hype to post-hype reality—and the pattern is always the same: the infrastructure persists, the noise fades, and the interesting work happens in the quiet period after everyone stops paying attention.

Why Physical? Why Now?

After three decades in digital spaces, building platforms, backing startups, investing in emerging tech, I’ve returned to making physical objects with my hands.Back to what I learned as an Industrial Design student in college.

The work is generative, but not in the way most people understand that term. I write custom code for each piece. The algorithm generates a composition, layers, depth, color relationships. But then the digital becomes dimensional: laser-cut matboard that is hand-assembled into relief sculptures that exist in physical space.

Each work is one of one. No editions, no prints, no reproductions. What remains is a singular object that is tangible, material, touchable.

This isn’t a rejection of technology. It’s a synthesis. I’m using computational design tools with the same rigor I brought to Xbox.com or civic tech infrastructure. But the output is something you can touch, something that casts shadows, something that changes as light moves across its surface throughout the day.

There’s a reason I’m making this work now. After years of building digital systems that scaled infinitely, that reached millions of people, that optimized for engagement and virality, I wanted to make things that resist scale. Objects that can only exist in one place, owned by one person, experienced in one specific moment of attention.

Process is Provenance

Every piece I create includes documentation that reads like software provenance. The generative system is described. The fabrication process is detailed. The materials are specified. A README for the artwork.

The work bridges two worlds: computational precision and manual craft. Code and paper. Algorithm and hand assembly. It’s not about choosing between digital and physical, it’s about understanding what each medium does best.

Who This Is For

These pieces are made for a specific type of collector. Founders who’ve built products. Engineers with taste. Product leaders who understand systems thinking. Design-minded executives who care about how things are made, not just how they appear.

People who’ve been inside technology companies understand something: great work is always systematic. Whether you’re designing an interface, building a platform, or creating a physical object, the underlying logic matters. Process creates quality. Constraints generate creativity.

My collectors tend to be interesting people who’ve seen multiple innovation cycles. They were early to things that mattered. They understand that the most interesting work often happens in adjacent spaces, at the intersection of disciplines, in the gaps between established categories.

What Happens Next

If you’re still reading this, you probably understand why someone would spend twenty years in digital spaces, then return to making physical objects. You recognize that code-generated dimensional relief isn’t a contradiction, it’s a synthesis.

The work exists at the intersection of everything I’ve learned: systematic thinking from Xbox, infrastructure design from civic tech, early-stage pattern recognition from angel investing, and a fascination with innovation that started with a solar car in Hawaii thirty years ago.

Each piece is a marker, a physical artifact of a specific moment in a long exploration of what it means to make things that matter. Not things that scale. Not things that optimize for metrics. Just singular objects that reward sustained attention.

Supporting Causes That Matter

Across gaming, civic tech, Bitcoin, NFTs, and AI, one thread has never changed for me: technology is only interesting when it serves people and the causes they care about.

The solar car in Hawaii was never just about engineering. ActionSprout was never just about metrics. The incubator was never just about startups. Each was an attempt to build infrastructure that made it easier for people to act on what they believe in.

The same is true of my artwork.

These one of one generative reliefs are not neutral decor. They are anchored in a belief that the things we choose to live with should reflect the world we are trying to build: intentional, well crafted, and quietly aligned with our values.

That is why my current practice is connected to a broader commitment to support nonprofits and causes through gifts of 26 artworks in 2026.

I can’t do this alone.

If you know of an organization, school, grassroots group, or foundation that would genuinely benefit from an artwork donation for an auction, gala, or fundraiser where a piece like mine could help them inspire hope and raise more, I would be deeply grateful if you’d share this offer with them or help introduce them to me.

https://studio.shawnkemp.art/donation-request